Chapter One

Michael Daniel

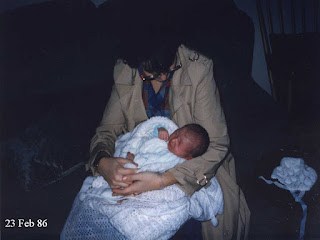

Robert Norton decided to arrive amongst us on a Monday morning in February, in

the snow. To those people who don't live in a busy commuter belt, that might

lack significance. To those who do, the fraught nature of a trip along an

approach road to junction 11 of the M25 at 8am

on a Monday will be only too easy to understand. The pregnancy had not been

particularly easy - I had lost Michael's twin early on, and now he was over two

weeks' late in being born - so I had decided that a long and difficult labour

was probably on the agenda and hadn't bothered to rush too quickly into the

maternity unit.

However, I had

not banked on Graham deciding to feed the cat, make himself a four-course

breakfast, prepare several rounds of sandwiches, collect a copy of 'The Times'

and make various other preparations as if for a siege before leaving the house.

Hence by the time we were stuck in the traffic jam along the A320 I was being

forced to lie about the frequency of contractions rather than have both of us

panicking uncontrollably. By the time we arrived in hospital, Michael had

seemingly gone off the idea of being born at all, and eventually was delivered

by forceps at 12.27pm, weighing 7lbs 13oz, and was rushed away as he seemed

reluctant at first to breathe. After a few minutes, the midwife returned him to

me, with the prophetic words, ' This one's been here before……….. look at the

way he's watching everything.'

I had never

seen any young babies before, much less a brand new one, and as I took this

grave little stranger into my arms I was awe-struck and strangely moved by the

way in which he looked up at me. He and I surveyed each other carefully; he was

obviously studying my face intently, recognising my voice but quite clearly

uncertain as to whether or not I was going to be up to the job of being his

mother. That was look I came to recognise well - and so did many others. It was

never a case of being criticised, or even of not being good enough; but you

always knew when Michael looked at you with that very direct gaze that he KNEW

the answer to the unspoken question.

Unfortunately,

in those early days, the answer was painfully obvious to both of us. Being a

total novice I didn't know anything about babies at all. In 1986 it was the

norm for mothers to stay in hospital for five days - and thank heaven I did,

for if I had gone home in the first couple of days I doubt Michael would have

survived until the weekend, never mind to age 14! It was only when Christopher

was born, exactly three years later, that I realised that in those first couple

of weeks I had NEVER picked Michael up to cuddle him; it never occurred to me

that I could. I picked him up to feed him or to change him, and then I put him

down again. I often wonder if that was one of the reasons why he was such an

un-tactile child. Furthermore, I am rather ashamed to confess that I seriously

underfed him in those early days. He was bottle-fed and because in the first 48

hours he only took 2 or 3 ounces from each bottle, I thought that was all he

should be taking. Demand feeding hadn't permeated through to my brain, for some

reason. After he screamed his way through day 3, the sister picked him up,

swaddled him tightly, gave him 6 ounces of milk, winded him and he settled

straight off to sleep. 'That's more like it!' she said. 'I wonder what was

wrong with him?'

In any case,

all of that became academic very quickly as Michael gave us the first of what

would turn out to be a lifetime of medical emergencies. On Saturday, February

22nd, aged five days, he was getting ready to be discharged. I had

started to get him dressed in his own clothes for the first time and had the

carry-cot all ready for the Big Trip Home. The registrar came in to assess him

for discharge and performed all the usual tests. She was listening to his

heart, and I wasn't paying too much attention, when her face suddenly changed.

Then came the words that no mother wants to hear but which we became all too

familiar with:

'I think

there's something wrong here.'

Michael was

wrapped up in a warm blanket, a pram appeared from somewhere and he was pushed

straight across to the x-ray department for some scans and tests on his heart.

I was so shocked and distraught I didn't go with him; strange to look back on

that now, but I was busy shouting down the phone to Graham to come as quickly

as possible. By the time Michael was brought back to me on the ward, the duty

paediatric consultant had arrived at the hospital and come to see us. This was

the first time we met Dr. Richard Newton, a wonderful doctor whom Michael

always liked immensely, and for whom I frequently felt so sorry as over

Michael's short life he battled to make sense of the many and various - and

rare - illnesses which befell him.

Michael was

taken off to have an ECG because it was decided that he was very 'breathy'. I

hadn't noticed - as I say, I'd never been near a tiny baby before so in all

honesty I probably wouldn't have thought anything he did to be particularly

remarkable. The ECG machine could not be persuaded into life that afternoon,

and after another overnight stay and much discussion we were allowed to take

Michael home on Sunday afternoon, on the understanding that we would be back on

Monday for the ECG. We drove home through the snow and as I carried Michael

into the house it dawned on me again what a miracle the whole thing is; that

two of us - a couple - went into the

delivery room and three of us - a family - walked out. And of course that

process was to be cruelly reversed in another hospital room nearly 15 years

later.

Michael's

tests on Monday showed no abnormality in the actual chambers of the heart, so

the general opinion was that this was a straightforward murmur of a sort that

generally cleared up on its own as the child grew. Certainly Michael had

regained his birthweight within the first ten days and seemed to be doing quite

well. This was to be a familiar pattern throughout Michael's life; the initial

scare, the feeling that everything was under control - and then Michael's own

personal spin on the situation which always sent it belly-up when we least

expected it.

In this case,

although we were concerned, we were reasonably comfortable even though another

ECG in early March still didn't establish what was happening, and we simply got

on with the job of enjoying our baby. We had to set the alarm clock to wake him

up for feeds at night or else he would sleep through. Maybe I should have been

a bit surprised at that, but once again, I assumed it was fairly normal

behaviour and got used to staggering out of bed in the small hours to force

Michael awake to be fed. He was still putting on weight, and he had started to

smile from 4 weeks old and generally appeared to me to be a normal baby.

Another

echogram towards the end of March raised some more concerns; the murmur was

still there but 'not making a distinctive murmur sound' - and by now the

opinion was that whatever and wherever the hole was, it was also affecting

Michael's lungs. By two weeks later, he had stopped gaining weight and we were

asked to bring him back to St Peter's a few days later for a further echogram.

This time they located the hole - it was identified as a 'patent ductus

arteriosus '. This is a little valve which is open during pregnancy to allow

the blood to circulate around the baby bypassing the lungs, as obviously the

baby is taking in oxygen from the mother and not from the air. It is supposed

to close at the time of birth and as the baby takes its first breath. Frequently

it doesn't, but usually the hole will gradually seal itself as the child grows.

In Michael's case the hole was still open, and there was a lot of excess blood

in the left ventricle. Dr Newton was of the view that Michael would need an

operation at some stage to close the hole, and he told us that he would refer

Michael to the Brompton

Hospital.

Now we did

begin to worry and to watch Michael like a hawk. Of course, from my lofty

position as an ignoramus, I wasn't really certain what I was looking FOR exactly,

but I was determined not to miss anything. We began to worry if he cried in

case it put more of a strain on his heart and lungs. We worried if he DIDN'T

cry in case it was significant in some way. Meanwhile the recipient of all this

attention was continuing to be more aware, to make more sounds and to smile and

even laugh.

A week after

the last echogram we had a phone call from the Brompton saying that they had

had a cancellation for the next day, April 16th, and would we take

Michael up at 10am. Surprised but pleased, we went along and Michael had

another set of X-rays, ECGs and other tests. Then he was taken upstairs to a

much larger echo machine. While the results were being discussed, we sat

outside in the corridor feeding Michael. He was about halfway through a bottle

when the consultant came out; 'I'm sorry, Mr and Mrs Norton', he said, ' but

you will have to stop feeding Michael straight away. The ductus is so large

that Michael is in heart failure, and we need to operate on him right away. Fortunately

there is a space on the end of today's operating list……'

I think I

rather lost track after that and didn't really get the gist of much else that

was said. Now I am much better at it; I listen hard and then go to pieces

later. But this was one of the first times I had heard bad news and it was all

too much. For the surgical team, of course, this was a routine operation,

although not without risks. I remember meeting the surgeon, a huge man with

hands to match, and thinking to myself that I couldn't envisage how a man with

hands that size could operate on a baby's heart - which wouldn't have been much

bigger than a large walnut. Fine for playing Liszt, though, I decided.

Graham and I

were horrified that things should take such a sudden and unexpected turn.

Graham asked what the success rate of this operation was. 'About 80%,' replied

the surgeon. This meant that one in five babies could die from it. Neither of

us liked the sound of that, so we asked what would happen if we refused to give

consent. ' Then I'm very afraid that Michael will die quite soon,' came the

gentle but firm reply. So we signed the form.

Michael was

carried down to the theatre at 6pm

by a hospital porter - too small for a trolley - and the nurse accompanying

them suddenly ran back along the corridor and asked if he had been christened.

'Er….no,' I said, bewildered. She wrote down his chosen names carefully on the

back of her hand in biro as she dashed off again. Graham and I wandered into

the hospital chapel and sat there for a while, making plea bargains with God. I

suppose that over the next few years, God must have wondered why we kept on

doing it - after all, there were no hard promises coming forth from His

direction. Funnily enough, at that stage, neither of us was confirmed, although

I had always been a regular churchgoer. Graham hadn't even been christened; for

both of us Confirmation would come in the next few years. Meanwhile, this was

the first of many hospital chapels to receive visits from us.

The next 36

hours in Intensive Care were as traumatic as one might expect, although from a

medical point of view Michael was making good progress. Once down on the

babies' ward, we quickly made friendships with other parents in the same

situation. I sometimes think that it is only another parent in that state at

that time that really understands how you feel. And of course there is ALWAYS a

child worse off than your own; a good perspective for anyone.

Michael

recovered quickly and was back home five days later. This seemed incredible to

me; and in fact we were told that babies take a day for every week an adult

needs to get over this sort of operation. Michael had a pretty ugly scar, which

meant he needed careful handling. We assumed the scar would fade, but it never

really did; even when he died, it still reached halfway across his back, just

as it did when he was eight weeks old. This scar was to prove a feature for

him. When he was at the Royal

Grammar School, some

twelve years later, an impressionable, nay gullible, young boy asked Michael

how he had got it. 'Well,' said Michael, 'I was surfing off the coast of Florida and there was

this shark…….'. One of the benefits of being so small and apparently frail, as

well as having a fearsome intellect and a reputation for being a 'straight kind

of guy' , is that people tend to believe you. Michael built quite a reputation

on this for a little while.

Once we were

discharged from the Brompton, delayed shock set in, I think. Looking back,

there I was, aged 27, having always done well at my grammar school by dint of

working hard. I went off to University where I didn't work quite so hard, but

throughout my life it had always been the case that if I wanted to know about

something, I looked it up in books and then applied the knowledge. That was the

case with pregnancy, more or less. I knew how I should look after myself and I

knew the theories on babycare. So I couldn't understand how I had managed to

'fail' at producing a healthy baby, particularly when you only had to turn on

the television or open a newspaper to see someone who patently had NOT looked

after their child and yet the infant appeared to be thriving. I just didn't

understand it, and I soon came to the conclusion that somewhere along the line

I must have done something wrong.

Before I could

think it through logically, though, we were already into our second health

crisis. Michael had come home from the Brompton on Monday evening. By Tuesday

night he was being very sick and acute diarrhoea. Late that night I phoned the

Brompton to ask whether it could have anything to do with all the drugs which

he had been given whilst there. The answer was quite definite: no. By the next

afternoon, we were back in St Peter's, trying to correct the dehydration, which

was not helped by the fact that Michael had lost a great deal of weight in the

previous couple of weeks. Ironically, he was in St Peter's longer than he had

been in the Brompton for his heart surgery. By the time he came home again, we

all felt as though we had been through a war. Nevertheless, as far as we were

concerned, it had been a traumatic start but he had recovered, and was not

expected to have any further problems. Certainly, he continued to achieve all

his developmental milestones.

In July, he

was christened during the morning service at St Nicholas' Church in Pyrford. It

was a very special service; the sermon focussed on the meaning of Michael's

name - 'chosen by God' - and the relevance of that, given how ill he had been.

It was around this time that the vicar had come to see me to talk about Michael

and to bless him. When I said how distressed I had been that my child had been

so ill, he made the comment that Michael wasn't mine, he belonged to God and I

was in fact taking care of him - he was on loan, so to speak. I have often

returned to that conversation in the light of future events and thought that

maybe there was a grain of truth in it. I discussed it with Michael himself, on

one occasion. Michael said to me,'Well, actually I don't want to belong to OR

be loaned by anyone. I will choose when I go back to God, if I possibly can.'

And what prophetic words they turned out to be. St Nicholas came to play an

important part in our lives; after Christopher was born in 1989 I became

Director of Music to the Parish for five years. My sister was married there, my

mother's ashes were interred there, and now Michael himself lies there, under a

Christmas tree on the hillside, just as he had always wanted ( give or take the

odd mausoleum…….. of which more anon).

By the Autumn,

it was certainly noticeable that Michael wasn't growing very much. In fact, he

was no bigger at one year than he had been at six months - but he was walking,

starting to talk and extremely lively, so again, we were never too worried. We

had a lovely Christmas with him, as all first Christmases are, but by

mid-January we were back in hospital again, this time with a high temperature

and breathing difficulties. Nobody was certain what was wrong; his blood counts

were low, and he had a few small patches on his lung, but otherwise there was

nothing much to go on. He came home for a couple of days, but by January 28th

was back in hospital. This time the diagnosis was pneumococcal osteomyelitis (

a severe bone infection which can be extremely serious if left untreated); he

had been limping and his temperature was very high. Plenty of intravenous

antibiotics sorted the problem out eventually, and he was home in time for his

first birthday on February 17th …… and a bout of chickenpox to go

with it. I still thought we had simply been unlucky; even so, I still found the

sight of this little chap in hospital so very distressing. Michael, though,

never showed any signs of being unhappy. In the evenings, we would wait at the

corner of the ward watching him as he fell asleep, quite unperturbed by us not

being there, before going home for the night. He was always - and he remained -

totally co-operative with the nursing staff throughout all the various

procedures he had to endure. Meanwhile, in his brain he was planning his own

revenge - by May we were back in the hospital again. This time, he was refusing

to eat. Our GP thought the osteomyelitis had returned. Dr Newton thought,

probably correctly, that Michael had

simply worked out that food was the one area of his life that he had control

over. Eventually he 'agreed' to eat a little bit - and then I realised that he

would often not swallow it. He would 'store' it in his cheeks like a hamster,

and when he had his after lunch nap I would have to empty out the food from his

face!

Michael hated

food throughout his life. He didn't enjoy taking time out from whatever project

he was engrossed in at the time to come to the table, nor did he find anything

pleasurable in the social side of meals, either at home or in restaurants. I

still wonder if it dates back to his first few weeks before his heart surgery,

when feeding made him so tired and breathless and simply wasn't a good

experience for him. Throughout his life, his diet was never wider than fish in

breadcrumbs, party-size sausage rolls, chicken nuggets, yorkshire puddings,

omelettes and roast potatoes. And mustard, bizarrely. I tried EVERYTHING. Every

ploy known to mothers. I left food around the house, I withheld treats, I

bribed him ( hopeless, that one) and we saw doctors, psychologists, homeopaths

and every other type of -ologist and -path barring psychopath. We didn't need

one of those. That was me after several years of this. And yes, I have

frequently asked myself whether this contributed to his cancer. But to be

honest, I see little point in beating myself with that particular stick now; I

had all that out with Michael and he simply ignored it. He said he hated most

food and that was an end to it, as far as he was concerned. Fortunately, by way

of relief, God sent us Christopher who was different from Michael in every way

possible, not least in his capacity to eat for Europe,

should it ever become an inter-continental sport. The spicier, the better. So I

must have done something right SOMEWHERE along the line. One of the most bizarre

aspects of Michael's treatment for cancer was seeing him eat and eat whilst on

steroids. He stuffed biscuits and chocolates and pizza incessantly - it even

amused him. I remember one evening where he had eaten so much he lay flat on

his back on the settee, groaning that his stomach felt near to exploding. He'd

never before felt full!

Chapter 2

By the time

Christopher was born, 5 days after his big brother's 3rd birthday in

February 1989, Michael was quite clearly displaying all the personality traits

which would mark his older childhood - great intelligence, a sparky sense of

humour and a huge interest in everything going on around him.

He was

fascinated by the concept of a new baby in the house. " My mummy has a

baby in her tummy" was a sentence he used as the ultimate put-down if he

felt any other child had too much to say for himself. I was concerned that

Michael had started playgroup just three or four weeks before the birth, but he

took it all in his stride, rushing in with his Thomas the Tank Engine lunchbox

and appearing to make friends quite happily. I was more worried when he decided

to rename himself 'Peter' at this point, and would write 'Peter' on all his

paintings and other pieces of work. Unsurprisingly, not many of these arrived

home in the early stages of his playschool career. Peter's mother, on the other

hand, was probably overwhelmed by her son's artistic output.

Undoubtedly

Michael felt pushed out in the first few days of Christopher's life. On the

first night at home, Michael - who never woke in the night - came into our room

on several occasions, turning up finally at 6.45 am. Graham told him it was FAR too early to be waking

up - and then my mother, who was staying with us for a few days, found him

kneeling at the end of his bed in tears. I got up and went into his room, and

after a few stories cuddled up together in bed he cheered up. He was already

starting to read at this point, he had a prolific book collection and was

always keen to go to bed in the evenings because he would put a story tape on

his cassette recorder and then sit, listening, while he leafed through his

books. He would read to the baby from a very early stage, enjoying being the

'big brother' despite his very tiny stature.

It was also

clear that he was extremely mature for his age, and two incidents stick out in

my mind from his pre-school days. Graham was away working in Zurich for a few days so I was on my own in

the house with the boys. Christopher awoke at 6am one morning for his feed, and when I came to change

his nappy it turned into one of those experiences which requires all involved

to have a total change of clothing. I switched on the teasmaid and went to our

walk-in airing cupboard, not realising that Christopher was crawling along

behind me. As I was in there, he stood himself against the door, which slammed

shut. With no handle on the inside, I was stuck - and the teasmaid was about to

fill the teapot with boiling water, making a noise which would attract Christopher's

attention.

Being

claustrophobic, I decided that panicking was an appropriate response at this

point. I shouted loud enough to waken the dead - and Michael was impossible to

waken. Fortunately, he wandered out onto the landing. Aged just 3, the following

conversation took place:

" Mummy?

Where are you?"

"In the

airing cupboard……….."

"Is that

sensible?"

"No. Now,

Michael, I need you to let me out."

"I'm too

SMALL, Mummy, I'll have to find something to climb on……"

Parents of

toddlers will appreciate that, at this moment, most 3 year olds would have

realised that this was a golden opportunity to eat chocolate/watch television/

draw on the walls in wax crayon or do anything else which is usually banned. I

feared exactly that. But to my surprise, Michael found a stool and, somehow,

managed to open the door. He was totally taken aback by the enormous hug he

received.

"But

Mummy," he said, "If I COULDN'T have done it I would have dialled 999

and told the policeman to come and get my Mummy out of the airing

cupboard!"

Sang-froid as

only Michael could show it.

On another

occasion we were discussing aeroplanes. He had a fine collection of Airfix

models, mostly built by his adoring grandfather. I told Michael I didn't like

flying AT ALL. (Something to do with being the daughter of an air traffic

controller, probably.) My son looked at me pityingly for a few minutes, before

launching into a detailed - and, as I discovered later, not being too clued-up

on these things - entirely accurate description of how an aeroplane gets off

the ground.

This

precociousness was not always beneficial. After his 3 1/2 year health check ( a

kind of paediatric MOT ), Michael and I were referred to the Child Guidance

Clinic. The doctor who had carried out the assessment had felt that Michael did

not relate to other children in the same way as most toddlers, preferring to

talk to adults. Too right! One session at the clinic told us what we had known

all along - that Michael was far too keen on books and numbers to want to spend

much time playing. And so it remained.

Chapter 3

Michael was

still very small for his age when he started school, but the hospital was quite

happy at this stage simply to monitor him a couple of times a year. He began at

the local state primary school in January 1991, shortly before his fifth

birthday. He started on a Monday morning, and on the Thursday of that week,

January 10th, I took Christopher with me on a visit to the Rector's

wife. She and I were having coffee while Christopher played with her two year

old twins. We discussed Michael's less than happy start, and I remember saying

to her that we had always been told that once he'd made it to school, he would

probably settle down healthwise and live to be 100.

Within ten

minutes, her phone rang. I heard Shelagh say, 'Yes, that's right, she IS

here………', and then she re-entered the room looking very pale.

'Michael has

had some kind of accident in the playground,' she said. 'The ambulance is just

leaving the school now.' I abandoned Christopher to her and ran for the car.

Later on, I would have no idea where I had left him; I have no recollection of

getting to the hospital at all, although I confess I recollect only too well

reversing into a bollard outside A&E.

Michael was

lying on a bed in Casualty, his headmistress sitting next to him, with his eyes

tight shut. He had been sick, but when examined by a doctor was found to have

no extraneous mark or bump and I was allowed to take him home. Graham arrived

back at the house shortly afterwards, and we were both concerned that Michael

didn't seem certain of who he was and was still being sick. I rang the hospital

again. 'Give him Calpol for his headache and see what happens,' was the

response. By the afternoon I was very unhappy about him and decided to call out

the GP. He was a family friend and was able to see at once that Michael was far

from well. His eyes were not reacting normally, nor were his reflexes. Within

an hour we were back in hospital. This time Michael was x-rayed. The cause of his

symptoms was now obvious; there was a long thin fracture line running from the

top of his skull round the back of his head and edging into the temporal bone

behind the left ear. Apparently, Michael had been outside at playtime and been

with his friends on the 'wendy house' style climbing frame. He was on the top

step of the ladder when we think he must his banged his forehead very hard. At

that point he presumably passed out, since he went straight backwards off the

ladder and managed to fall onto the back of his head without breaking his neck,

suggesting he was very relaxed as he hit the ground.

The 'ground'

in question was the playground - made of tarmac. Although all the equipment in

borough council-run playgrounds in the local parks was set into soft surfaces

at this point, in the schools this was not the case. Surrey County Council were

of the opinion that a soft surface encouraged children to be over-confident,

thus making them more prone to accidents which would then result in more

serious types of injury. Good grief. We spent a lot of time trying to challenge

that school of thought - to no avail.

Januaries

never were very good for Michael.

He remained in

hospital for several days. Serious head injuries take a long time to recover

from, however, and have many side effects. Still, at least we were getting in

some practice for the brain surgery to come later. His sleep pattern changed

overnight. Always a good sleeper, he would never again find it easy to go to

sleep at night and he woke early from this point until the time of his

chemotherapy.

One of the

benefits of the illness, however, was that he was rather fragile for going back

to the rumbustious school playground, and for the rest of that half-term - his

first school experience - he attended the Hospital Teaching Centre at St

Peter's Hospital. This is for long-term sick children ( originally for

orthopaedic cases when the Rowley Bristow Orthopaedic Hospital was still in

existence) who are unable by virtue of their illness to attend mainstream school.

We were very lucky that this facility existed; in most areas, a child in

Michael's situation has to resort to home tuition for a couple of hours a week,

which can be very isolating.

Michael loved

it. He loved the individual attention but, even more, he loved the fact that,

because of the mixed ages and abilities, he could take each subject as far as

he was able. He never forgot it - and the one big benefit which cancer brought

him was the ability to go back to the hospital school and meet friends there -

and in a way he came full circle.

The skull

fracture marked the beginning of another set of medical problems. It must be

said right away that, despite having the most sophisticated of scans over the

next ten years, there was never any proof that the accident was related to all

that followed. Maybe Michael had a weak skull in the first place. He had a

large haemangioma ( a collection of blood vessels, like a red birthmark or port

- wine stain ) under his left ear and cheek, which wasn't really visible unless

he was hot or angry. THEN it stood out! All these things might have played a part. Now we'll never know. But later that year

( in 1991) Michael became ill again. He had a very high temperature and his

left ear - the whole ear - swelled to several times its normal size. This gave

us a huge laugh at poor old Michael's expense since he looked like a cross

between ET and an African elephant. Back into hospital he went; the diagnosis

was pneumococcal cellulitis and mastoiditis

and, just as with the earlier ostomyelitis, the treatment was high doses

of intravenous antibiotics. It was at this point that Michael became the

needlephobe that the staff of the 30 hospitals he visited in his life will

remember. Because he was so small and thin, it was never easy to find a good

vein. Trying to inert a canula was always a trauma for all of us and I learned

to dread it, pleading, cajoling, threatening and using all sorts of wholly

inappropriate bribes to try to help things along. It never did.

On this first

occasion, the cellulitis was brought under control pretty quickly. Yet again,

we regarded it as an unfortunate one-off. Sadly that was not the case. Michael

had several recurrences, each one spreading swifter than the last and each time

involving more of his face. It happened about every 18 months - once on a choir

tour to Poole ( Poole General Hospital ), once on holiday in France (

Draguignan Hospital ) and a couple of times at homes. The last time was the

worst - for a while we feared he might lose the sight in his left eye, so

serious was the swelling behind it.

He had tests

at Great Ormond Street to see why he kept getting infections, but nothing ever

came of it. I decided he was a 'Friday afternoon child' - constructed from

cheap parts just before God finished work for the weekend.

Chapter 4

Of course, all

of this simply states what was wrong with Michael but in no way

illustrates all that was right.

By the age of

6 he was clearly far from happy at the local state school and we moved him to a

prep school in Guildford which was also the Choir School for Guildford

Cathedral Choir. We had taken him to an open day, and when he heard the

Cathedral Choristers singing, he turned to me and said, ' I want to do that.'

He had been playing the piano since he was 4, despite having tiny hands, but I

always felt his heart wasn't really in it. I was proved right when he chose the

cello. From the beginning it was clear that this was where he was meant to be.

By the age of 11 he had passed Grade V on both cello and piano - he never fell

below high distinction marks on the cello, nor did he rise above low merit

marks on the piano! Undoubtedly one of the factors here was the strong

relationship which he forged with his cello teacher, Annelies Scott. A

wonderfully open young woman with a remarkable resemblance to the Vicar of

Dibley and the same warm and welcoming smile, she inspired Michael, as she does

most of her pupils, to great things. She always said that she only had to worry

about the technical side, that the musical side was already there in spades.

She was right in lots of ways, but her exuberant enthusiasm was a perfect foil

to Michael's quiet nature and the result was wonderful.

In Michael's

last two weeks, when he was in hospital, I put on a CD of the Bach cello

suites. On one occasion he became distressed and said, 'No! Not that,

please…..' On another occasion he smiled dreamily.

'I love that

sound.'

'Michael, do

you remember when you played this piece?'

'No! Did I

play this instrument?'

'Yes, you did,

Michael, you played it so beautifully…..'

'I remember

something…… there was a lady…… she was lovely……… yes, I remember her……….' And

he smiled, gently.

He passed his

audition for the Cathedral Choir by singing 'Jingle Bells' in the school choir

practice in September, 1993, and fell instantly in love with the whole thing.

He was 7 when he joined, and the only probationer at that time. One consequence

of his limited stature was obvious at once - he was too short to see over the

choir stalls. It was a source of amusement to many of the congregation as the

years went by when, first, his eyebrows appeared, followed several months later

by the eyes, nose and finally, by the time he had been in the choir for several

years, his mouth. He wasn't too easy to see by the time he left, either.

Despite that, he was always treated with jocular kindness by the older boys.

Andrew Millington, the organist, would say later that he could see Michael had

something about him from his earliest days, and, in Andrew, Michael found

someone else whose influence over his life would be considerable. After all,

Michael spent nearly six years in the Choir - almost half his life - and

without any shadow of a doubt it was the thing he felt most committed to apart from

the cello.

He was totally

in awe of everything and everyone, and from the first day became consumed with

ambition to be a Head Chorister. He took it all extremely seriously and,

although he had been going to Church all his life, found the High Church rituals

fascinating. He became so used to strange things going on at the Altar that

sometimes we were only aware after the event how much he took in his stride.

One evening

after Michael had been singing at the Installation of the new Bishop of

Guildford, we had brought him home late and put him to bed before going

downstairs to watch the news. There, before our incredulous eyes, we heard all

about the protest by 'Outrage' supporters, when several people had burst

through the Sanctuary doors, chanting and shouting, before being removed by a

number of people including both the vergers and some of the more eminent of the

local constabulary who had thought they were simply having a pleasant evening

out.

Graham and I

looked at each other and made for the stairs. 'Michael,' we asked, 'Were there

a lot of people in the Sanctuary shouting and waving banners this evening?'

'Yes,' said Michael, surprised to be asked, ' And lots of people running about

for a while, too.'

'Didn't you

think it was odd?'

'No, was it?'

The sang-froid

again. Nothing EVER fazed Michael, really. I don't ever remember seeing him

incandescent with joy or sorrow; certainly extremely proud and content, but

never, ever 'jumping-about happy' such as Christopher ( or I!) might get. I

truly think that, as the midwife had said, he'd 'seen it all before'.

He was

surpliced in September 1994 after two terms' probation and took his place as a

full chorister. While a probationer, he had studied all the basics of the trade

with Geoffrey Morgan, the sub-organist, on Monday mornings whilst the rest of

the choir rehearsed with Andrew, and therein lay the foundations of a respect

for Geoffrey that lasted throughout his time in the Cathedral until his

funeral. Michael always said that he learned most of his music theory in these

lessons, as well as developing a deep love of the psalms and their chants. It was no coincidence that Michael was to ask

Geoffrey to play at his funeral.

'I know what

music I want and I like the way Mr Morgan plays it,' was what he said.

Having said

that, he knew only too well how much he owed to Andrew. He sang his first solo

aged 10, and after that sang more and more of them. He had a very high, pure

voice - not a big voice by any manner of means, but he was invariably reliable

and always faultlessly in tune. Hearing that voice soaring above me in the Nave

of Guildford Cathedral as he effortlessly hit one top C after another in the

Allegri 'Miserere Mei' on Ash Wednesday, February 25th 1998 - well,

that is a memory etched in gold.

Being the

littlest chorister brought its own set of dilemmas. Shortly after starting in

the choir, he lost a double tooth. The Tooth Fairy obligingly swapped said

tooth for some derisory amount - I forget the going rate at the time. Michael

appeared for breakfast.

'Cor, Mummy!'

he shrieked. 'Wait till I tell the other choristers about THIS!! The Tooth

Fairy has been and left me this money!!'

I anguished

all over my cereal. To maintain the innocence of childhood or to subject my

beloved baby to the ridicule of lofty 9 - 13 year olds? Reader, I destroyed his

innocence. I can still see his crestfallen little face now. On the bright side,

of course, this honesty saved his father several pounds in the following couple

of years! In truth, I suspect that particular bunch of boys would have been

quite gentle about it. One of the biggest joys to Michael about the Choir was

in being part of a team; of course, at a day school this was always going to be

a less powerful element than Christopher was to encounter by boarding as a

chorister later on, but nonetheless, to Michael, it was an important factor.

Some of

Michael's own thoughts on the subject are recorded here. All the choristers at

Guildford are sponsored, by which I mean their choristerships are paid for,

either by an individual ( or group thereof ) or by an organisation. This isn't

a cheap thing since the choristers in effect receive one term's remission from

their school fees in return for the service they offer to the Cathedral.

Michael was sponsored by the Friends of Cathedral Music, an organisation

devoted to supporting and promoting the tradition of choral music on our

Cathedrals. Their local representative asked Michael if he would like to write

a short article on being a chorister for their newsletter, and this is the

result. Christopher, once again feeling a bit left out, said, 'Can I write one

about being a chorister's little brother?'

And so he did. Interesting to read Christopher's contribution when you

think that less than three months later he had passed an audition to one of the

top boarding school choral foundations in the country!

Academically,

too, Michael was up there with the best. We had had a full assessment done by a

child psychologist before changing schools - in fact it was at her suggestion

that we moved him. Everyone was in agreement that the large classes at the

local school did not help him; once we discovered that his IQ was well over

140, we realised that we needed to encourage him in all sorts of directions.

Having said

that, honesty requires me to say right away that Michael always was a lazy

toad! He always did the absolute minimum for homework - it was finished,

invariably, but he never walked 'the extra mile' - or even the extra inch, come

to that. When asked about it, at an early age, he said, 'But it's all in my

head! I don't need to write it down as WELL!' Indeed, in his last illness, he

was honest enough to say that one of the benefits was not having to flog his

way through acres of homework. He died before he had to get to grips with any

GCSE coursework - and he always knew that that would have been a huge source of

contention between the two of us.

Still, in

terms of raw intelligence, Michael was hard to beat. He sat the 11+ Entrance

Examination to the Royal Grammar School, Guildford, and was invited on the

basis of the results of that, to sit the scholarship exam. Fortunately for him,

it didn't involve any revision or learning; it consisted of verbal and non -

verbal reasoning, various forms of IQ tests and such things as reconstructing

models from apparently random shapes. This was all grist to Michael's mill. He

had already been awarded a major music scholarship; now the two were rolled

into one as Michael was made a King's Scholar. This was something of which we

were all inordinately proud. Michael played on this pride shamelessly and

somehow managed to wangle out of it a new computer for the family. 'After all,'

he said, 'Just think how much money I have saved you on school fees!' And he

was right. By the time he was Head Chorister, his choral scholarship and King's

Scholarship together equalled his total school bill.

Not content

with that, he also passed the 11+ exam for Eton College. This was all beyond

the wildest dreams of a couple from a state grammar school and the local

comprehensive. Even a chorister son at a prep school was a novelty to me. Eton

College seemed way out of our league! Nonetheless, Michael's musical talents

opened doors for him, and it was clear that he was going to be a strong

candidate for a music scholarship to Eton at 13. He moved from his prep school

to the RGS aged 11, in September 1997, where the Music Department was able to

provide him with far more challenges, but at this stage we were still allowing

for the possibility of him moving across to Eton at 13. The thought of making

this decision taxed Graham and I greatly over the next two years, but Michael

wasn't too troubled. By the time we had to make the final choice, Michael had

decided that he simply did not want too board. And that was the end of it. The

prospect of turning down Eton College seemed bizarre to me; but somehow these

things have a habit of turning out for the best - and, as it transpired, thank

heaven he stayed at RGS.

Chapter Five

In fact, one

of the deciding factors in the education issue was Michael's health. Again.

1996 was an

extraordinary year for our family in many ways. In January, my piano duet

partner and I flew out to Tokyo to take part in the International Piano Duo

Competition, where we won First Prize in the piano duet section. This was a

huge event in my life, something which I felt I had been working towards for

many, many years, and so I was thrilled when Michael and Christopher were

bursting with pride on my return home….. until I realised that they were more

interested to know what I had brought them back in the way of presents!

Then, in

February, Christopher moved into the spotlight for a while by taking it upon

himself to have a voice trial. I had made two assumptions:

1)

the boy had a voice like a duck

2)

he would wish to share this with

the Guildford Choir, alongside his brother.

In fairness to

me, this wasn't because I had actually heard Christopher, really, it just

hadn't really occurred to me that he might want to do it particularly.

One evening, a

week before Christopher's 7th birthday, Graham came home with a copy

of 'The Times'. He read Michael an article about the Choir of the Chapel of St

George, at Windsor Castle. Michael wasn't overly interested but, to my

surprise, Christopher asked when the Voice Trials were. Two weeks' time

appeared to be the answer.

'But do you

WANT to be a chorister?' Not an unreasonable question given the article he had

written for the FCM magazine not that long before!

'Yes I do -

but NOT with Michael. I want to go somewhere different.'

This presented

all sorts of problems; for a start, he was at the Choir School for Guildford

Cathedral, and there are strong protocols about anything which might be seen as

'poaching'. Secondly, neither Graham nor I had any desire to see our 'baby'

boarding. Still, I felt I couldn't refuse him the chance. 'After all,' I

reassured Graham, 'I don't think he can really sing!' Huh.

I selected a

song which I knew he liked - and I am given to believe that not too many

would-be choristers have offered 'Cabbages fluffy and Cauliflowers green' as

their chosen song! - and set to work. We only had limited time. Then, to my

utter amazement, on the Wednesday before the trial, Christopher suddenly said,

'I think I'll use my proper voice now………'

And that was

when I found out he could sing.

He passed the

voice trial. Graham and I then had our first major disagreement in fourteen

years of marriage. Graham felt he couldn't allow a child to board; I felt he

should be given this chance since he so obviously wanted to take it. In the

end, Christopher said he wanted to look around the school again - after which

he simply insisted.

Michael

watched all of this with interest. He had never considered his brother might be

gifted or self-motivated enough to take charge of his own life - especially at

the tender age of seven! He began to look at Christopher in a new light - and,

of course, once they were both choristers there was an endless source of

conversation between them, most of which was of the 'my choir is loads better

than your choir' variety.

When

Christopher started his new school at Windsor Castle in September, 1996,

Michael was at first quite devastated. Eventually he learned to enjoy the

benefits of our undivided attention and would resent it rather when the 'cuckoo

in the nest returned', as he put it! Against that, he disliked the focus that

his brother's absence allowed us to put on his homework and cello practice.

There was no doubt, too, that in many ways he was jealous of the opportunities

which were open to Christopher as a member of a high-profile choir. Although

his commitment to Guildford Cathedral and its Choir was total (it came before

EVERYTHING else in his life ) he was undoubtedly envious when he saw his

brother singing on a television broadcast with Jose Carreras, or at Prince

Edward's wedding. It wasn't so much that he thought he had made the wrong

decision himself, for as he said he had never wanted to board. But he

appreciated what Christopher had, and in some ways wished he had that too. He

always had a secret hope that the two choirs might sing together at a service

or a concert. In the end, of course, they did - at his funeral.

So it was an

interesting year for Michael, and in some ways a good one. At Easter, the

Cathedral Choir went off for a two week tour of some of the southern states of

America. They had a wonderful time, staying in hotels and with families.

Michael was always lucky with host families, and on this occasion near Atlanta

had a night out at an ice-hockey match, which he thoroughly enjoyed. Unusually

for him, he achieved the whole tour without a single episode of illness, for

which Andrew Millington was profoundly thankful, despite having roped in a

choir mother who was also a GP to come along in case of disaster! Then, in

August, we all flew out to Florida for the holiday of a lifetime before

Christopher went away to school. We had a week with Mickey Mouse, a week in the

blissful surroundings of Marco Island and a few days in the Keys. It was the

most wonderful time, truly a holiday which we all looked back on with huge

affection. The boys were in their element.

Christopher

went off to St George's on the first Sunday of September. The house was a very

quiet and unnatural place to be that night! I started a new job myself that

week - as a peripatetic teacher at the Royal Grammar School in Guildford - as

well as being in charge of the music at the local state primary school. Michael

himself was just beginning his last year at prep school.

On Monday

September 16th, I had a telephone call to say that Michael had been

taken ill on the games field and was in the school sick room feeling very dizzy

and unwell, with an earache. I brought him home; he certainly looked poorly,

but there were none of the signs which always shouted 'cellulitis!' to me, so I

simply assumed it was some kind of ear infection. He had no temperature and few

symptoms beyond some dizziness. I left him in bed in the care of a friend while

I went over to St George's to see Christopher, who only went up to Evensong in

his cassock on Mondays and Tuesdays, so there were few opportunities to support

him. When I returned home, he was still not well and I thought I would take him

into the surgery if he still seemed distressed the next morning. Sure enough,

the next morning he was still clearly in some distress - in fact, every time he

moved at all, he was sick. By some act of Providence, a GP friend rang me very

early that morning and, when I described his symptoms, was adamant that I ring

the doctor straight away. Poor Michael - all he wanted to do was to lie flat on

the floor. Within a couple of hours he was on his way back into hospital, where

he was seen by another specialist doctor whom we had come to know very well,

and whom we all, particularly Michael, liked enormously.

Patrick

Chapman originally crossed our paths when Christopher was very young indeed and

having one ear infection after another. I was always very impressed that Mr

Chapman never reached automatically for the scalpel, but always looked to see

what options were available ( in that instance, the six or so weeks that

Christopher was on a mucus-reducing soya milk diet will remain with me as a low

point. The SMELL of that stuff!!!!! ). Christopher did end up with his first

set of grommets at the early age of 14 months, but at least it meant that we

had someone we trusted by the time Michael had his first ENT problems. Glue ear

in childhood is extremely common, so the fact that Michael had a myringotomy in

August 1992 was nothing to worry about. The following April, in 1993, he had

another operation in which four permanent molars were removed and braces

fitted; these teeth had appeared to be rotten, possibly as a result of earlier

illnesses, and it seemed best not to take any chances but to take them out. By

September of that year, he was having more hearing problems and this time the

'glue' was drained from both ears and grommets inserted.

On this

occasion I was severely put out. I had spent years and years taking Michael to

hospitals, hanging around in thankless waiting rooms and buying innumerable

cups of disgusting coffee. On this particular occasion, I had to be at a staff

meeting at my school, and I delegated the job of taking Michael into hospital

to Graham, as it was only a routine day case surgery. Imagine my wrath,

therefore, when I discovered that on arrival at the hospital, they were asked

if they could be followed by a photographer for the day! The hospital were

making a book called 'Michael's Day in Hospital' with words and pictures that

could be used to show other children what was involved in a day case operation.

There was 'Michael and his Daddy check in', 'Michael and his Daddy meet the

anaesthetist,' 'Michael and his Daddy go down to theatre', 'Michael and his

Daddy talk to the surgeon', 'Michael and his Daddy recover after the operation'

and, finally, 'Michael and his Daddy are escorted off the premises'. Michael

and his Daddy got a bit of a frosty reception when Christopher and his Mummy

heard all about it. I was, therefore, quietly amused on a return visit to hear

that the most common response to this book was, 'Why can't I have my

Daddy here with me too?!'

A few weeks

after this operation, Michael woke up one morning and said one of his ears was

leaking. Unusual, I thought. Not many seven year olds complain of leaky ears.

He was very insistent that I did something, and on inspecting his pillow I had

to admit that his ear was, indeed, leaking 'water' at a great rate. A trip to

hospital proved inconclusive but there were a number of serious implications,

not the least of which was the worry that this was cerebro-spinal fluid coming

from somewhere in the brain. After the initial drastic leak, there was a small

seepage of fluid for a few days, and then it simply stopped, as suddenly and

mysteriously as it had begun. Michael had x-rays of his head and mastoids at

the local hospital, which didn't show anything obvious, and then we were sent

to the Atkinson Morley hospital in Wimbledon for a CT scan. No one knew what

was going on. In the end, the conclusion everyone came to was that Michael

might have some rare allergy to the grommets, and they were removed in yet

another operation in October.

In retrospect,

maybe it was a leak of inner - ear fluid. And the reason for thinking that was

because of what was happening to Michael as he lay in hospital in September

1996. Patrick Chapman had never met a patient like Michael before. Over the

eight years that he took care of him, he was always amazed at the variety of

rare and inexplicable symptoms that Michael threw up. However, just like

Richard Newton, he patiently and doggedly tried to get to the bottom of what

was going on, because he felt - as Graham and I still feel - that somewhere underneath it all there must

have been some connection between all these illnesses. On this

occasion, though, he was quite clear about what had happened. Michael had had a

perilymphic fistula. In his oval window, deep inside his ear, a rupture had

occurred which had allowed fluid to escape from the labyrinth and out through

the ear canal. As a result, he could not keep his balance but was suffering

acutely from dizziness and sickness. The only way to stop the symptoms was to

have an operation to repair the hole; this involved taking a little piece of

fatty tissue from Michael's earlobe and patching the tiny hole.

This is not an

easy nor a particularly pleasant operation; although he recovered well and

quickly, the removing of the packing from Michael's ear was not a happy

experience. I sat there as Mr Chapman pulled at yards and yards ( so it seemed!

) of bandages and Michael got more and more hot, bothered and distressed.

Finally he had had enough. 'Why don't you just pull the rabbit out of there and

be done with it!!' he shouted. And I have to say it did look rather like a

magician's flourish. Afterwards, Michael and I laughed that his earlobe was

probably the only place on his entire body where he had any fatty tissue at

all!

Patrick

Chapman told us that a perilymphic fistula is an uncommon occurrence in

children. That, of course, surprised us not at all. By this stage in Michael's

life we were very accustomed to the nature of his illnesses. In fact, I

remember our GP saying to me on one occasion that whenever an article in the

Lancet or BMJ featured something very extraordinary, the

once-in-several-GP's-lifetime scenario, he'd shove it in a drawer and wait for

Michael Norton to turn up with it! On the other hand, in 14 years I don't ever

remember Michael catching a cough, cold or stomach bug. Common or garden illnesses

passed him by altogether. If he couldn't get a trip in an ambulance or a visit

to some esoteric tertiary hospital, it wasn't worth the bother, I suppose.

Nevertheless,

as I say, Patrick Chapman felt that there must be some link between the skull

fracture and this latest problem. This became of increasing importance as we

realised that, as a result of the leak, Michael had lost all of the hearing in

his left ear. We were unaware of this at first; it takes a while for the ear

canal to recover from the trauma of having an 'entire magician's hankie

collection' down it, as Michael put it. After that, the vagaries of the NHS

audiology department are such that between November and January Michael had

several appointments which were rearranged and then cancelled for various

reasons. He was convinced something wasn't right, and by January we were all

very unhappy. Finally, in exasperation, we contacted Patrick Chapman who

arranged for us to see his private audiologist. We were devastated at the

findings - Michael was totally deaf in his left ear with little or no prospect

of anything being possible to reverse that. And of course, our worry was that

the same thing might happen to the other ear. At least if the problem was

related to the fracture line running into the left temporal bone, then

hopefully it was restricted to one ear only. Even so, for a musician this was a

terrible blow. Have you ever sat in a great Cathedral with your finger in one

ear? Probably not, admittedly. Next time you go, try it. The distortion of

noise is quite unbelievable, and I perfectly understand Michael's distress in

the early days of coming to terms with it. He was certainly desperate to

protect his 'good' ear. For a musician to lose any hearing is a fundamental

trauma, and he was terrified of losing the other. If we ever went to a show or

a noisy function, he would always take an earplug to protect his right ear, and

going to discos or rock concerts simply wasn't something he was prepared to do.

What would have happened as he got older, I don't know. It was the first time

he ever expressed any feeling of unfairness or irritation with his health.

Patrick was, I

think, just as upset as we were. He never missed an opportunity to talk to

other experts in his field about Michael, and I know that Michael's notes went

with him to at least one American conference so that he could ask questions of

those who specialise in the minutiae of ENT. As a result of his diligence and

that of Richard Newton, we visited Harley Street surgeons, the Royal Ear, Nose

and Throat Hospital, the Atkinson Morley, Great Ormond Street and Southampton

General Hospitals. There was never any conclusive information to be had - but

Michael was always more than aware of how much work was going on on his behalf.

His trust in

Patrick Chapman was unquestioned. We had always assumed that the perilymphic

repair would be a once and for all surgery which would put an end to all the

problems, but 18 months later, whilst on another Cathedral Choir tour ( this

time to Amsterdam) he became very ill with a strange infection-like illness in

his left ear. He recovered after a while, but in August 1998 he became terribly

ill, this time on holiday with us in the South of France. I always found it

weird how he became ill away from home - one theory is that swimming every day

might have been a contributory factor if there was already a tiny leak in his

ear. I am not suggesting for a moment, of course, that for any Little Joe

Ordinary there might be a problem! (I would use Christopher as an example here

but I can't even begin to tell you about his medical excitement in the South of

France in 1995!!!) .

Whatever the

reason, Michael became so ill with cellulitis that we feared he would lose the

sight of his left eye, so serious was the swelling behind it. Again, his ear

was huge and swollen and the French doctors, who were wonderful, said we needed

to take him home. We put him in the car at our rented gite near St Tropez at

4am one morning and drove non-stop, with him nearly unconscious in the back of

the car, arriving back at the Royal Surrey County Hospital around fourteen

hours later. Thank heaven for the Shuttle and its helpful staff. They looked in

the back of the car and I think were so concerned about a corpse being driven

on if they didn't act quickly that we were waved straight onto the train.

Patrick

Chapman suspected another leak, but because of the location of the oval window

there was no way of knowing for sure without performing another surgery. We

knew Michael wasn't going to be up for that, and decided not to tell him until

a few days beforehand. When he found out he was absolutely furious.

Interestingly, though, he wasn't so cross with Patrick - he felt that if Mr

Chapman said he needed another operation then he needed another operation. He

was mad with us for not telling him and had no patience at all with the concept

of the fact that we were trying to stop him getting into a state for days on

end beforehand. He said it was HIS body and he had a right to know.

That was a

lesson well learned by us.

There were

plenty of people who advised us to have another opinion or to engage another

surgeon. At one point when there was a vague hint that Michael might need to

have preventative surgery on the other ear to avoid the same problem arising

there, the same remarks arose. As far as Michael was concerned, they were

non-starters. He said, 'It's about trust. I KNOW Mr Chapman is trying to do his

best for me, so I'll take my chances with him, thank you.' I tell you, if you

were a friend of Michael's you could lay claim to some fairly powerful loyalty

Chapter 6

In the summer

of 1998, Michael achieved his long-held ambition and was appointed a Head

Chorister in the Cathedral Choir. This was a source of great personal pride to

him, and he took the position extremely seriously. During the summer holiday

before his installation, though, he chalked up another first when he and the

rest of the Choristers sang at the BBC Promenade Concerts. Michael was especially

thrilled because he had a short interview in the BBC Music Magazine Proms

Special Supplement. His name in print - and in a significant journal! Not that

this was the first time. During the previous December, the Choir had sung at a

Charity Carol Service in aid of Macmillan Cancer Relief at the Guards Chapel in

Wellington Barracks. Amongst the eminent guests were Margaret Thatcher, Diana

Rigg, Hugh Laurie and Helena Bonham -Carter, and Michael was looking forward to

it because he was going to sing the opening solo. I think most of us would

confess to the hairs on the back of our necks standing on end when we hear

those first unaccompanied notes of a boy treble singing 'Once in Royal David's

City……………' soaring through a darkened Cathedral. Michael had sung this on many

occasions - the first at age 7, in our local Parish Church in Pyrford, just a

couple of weeks before he joined the Cathedral Choir as a probationer. By 1997,

he was very confident about it; he never went sharp or flat and the organist could

always strike up for verse 2 without worrying that Michael had strayed into an

entirely different key!

On this

occasion, Michael sang beautifully, the service went off without a hitch, and

he was getting out of his cassock to come home when a photographer from the

'Tatler' appeared, asking who had sung the solo. The resulting picture, of a

laughing Michael unbuttoning his cassock, appeared in the magazine in the New

Year, and we would never have known if Christopher's headmaster hadn't

commented on it. After that, Michael came in for a lot of friendly ribaldry on

the subject of his receiving hundreds of fan letters from well-connected young

women. Rather to his disappointment, he didn't even get one.

Thus by the

time he was installed and presented with his Head Chorister medal, on Sunday

September 13th, 1998, he was already a seasoned campaigner in terms

of solos and musical responsibility. He was in his second year at the Royal

Grammar School by now, and was coasting a little academically. Not because he

was so far ahead of everyone else, but rather because he was lazy. There were a

few lively evenings at home on the subject of homework, as I remember it.

Nevertheless, we knew how much the choir meant to him, and we had a small

post-Installation get-together with a few of his school friends and their

parents. Of course, his non-musical friends probably thought he was quite mad

to want to do it, but they always supported him and, as far as I am aware, no

one ever made fun of him because of his voice. In fact, even his toughest and

most macho friends seemed to have a rather grudging respect that he could do it

so well. And as Michael said, he was earning some money from it. Much better

than having to get up early for a paper round!!

I kept his

programmes and service sheets from every special service in which he sang, such

as All Soul's, Advent, Easter, Michaelmas plus all the occasional concerts at

which the choir performed. In addition to this, we kept all the newspaper

cuttings, school concert programmes, bravery certificates from hospital ( lots

of those! ) and other memorabilia. I have a large box file for each year, and

one of the pleasures and sorrows of researching this book has been looking over

all Michael's achievements. I have done the same for Christopher, too. I cannot

recommend it highly enough. A couple of years after Michael was born, my father

presented me with a series of scrapbooks containing all my own press cuttings,

together with all my certificates from music festivals and exam report sheets.

It's my life story, I suppose, and I was always very determined that I should

be the archivist for my children until such time as they could take it over for

themselves. Michael was very keen on the idea; indeed, I have just picked up

from the box marked '1998' details of services for Sunday, January 18th.

The setting for Evensong that day is Tippett's St John's Service, and there is

a note in the margin written by Michael that says 'I did the solo in the Nunc

Dimittis'. It is a very difficult piece of writing and I was never sure that

Michael was singing the right notes. But later on that particular evening I

remember very clearly that Andrew Millington phoned me at home to say how

wonderfully he thought Michael had sung. Apparently it was all absolutely spot

on. And here is another piece of paper - a review of that concert in the Guards

Chapel, Wellington Barracks, taken from the Internet:

'The concert……. opened with the traditional 'Once in

Royal David's City', the first verse of which was sung by Michael Norton. His

beautiful voice, heard in the stillness of the candlelit chapel, set the tone

for the evening.'

I would never

have remembered half of all of this. It doesn't bring Michael back - but it

keeps a lot of him far more alive in our memories. We are so very lucky to have

all this material; not many parents would have so much.

Meanwhile, at

the RGS, Michael was getting into another of his loves - drama. In his first

year, the school mounted a production of 'Oliver!'. Michael would have loved to

have played Oliver and his tiny frame and treble voice well equipped him for

the part. But there was no possibility of him fitting in rehearsals around

choir practice, and he had to abandon the idea. Instead, he became involved in

his year group's drama project. He was actually very good. I watched him in one

sketch and I had been watching for several minutes before I realised that the

old lady in a wig was my son. The other thing about that evening was that one

person dropped out of the show with only two or three days to go. Michael

learnt the words in half an hour. That was why I should have realised something

was wrong when he was having problems learning some words in December 1999.

Hindsight….. a wonderful thing. Michael looked forward with great enthusiasm to

being able to get far more involved with drama once he left the choir; of

course, that was not to be.

So his second

year at the Grammar School was dominated by his Head Chorister commitments.

Pulling out the Cathedral Newssheet for the day of his installation, I see that

the anthem at that first service was 'Ubi Caritas' by Durufle. Interestingly,

it would also be the last anthem he sang as Head Chorister. And, of course, it

was the anthem he chose for his funeral. I wonder if he knew. Looking through

this box, which is full of the service sheets from just his final year, I see

how many solos he did sing. I don't remember it that way; another good reason

for keeping all this paper. Of course, there are now so many poignant things

about it. Here is the Evensong sheet from November 8th, 1998, for a

service attended by members of Marie Curie Cancer Care. One of the hymns is 'He

who would true valour see' - one of Michael's funeral hymns. Who would have

thought that, two years later, we would be using the services of these

wonderful nurses? I always think it is just as well that we can't see into the

future. But nice, too, to know that Michael was already repaying a debt he

didn't even know he would owe.

Michael did

all sorts of things that term; he made a demonstration radio advert for a

student at Surrey University as part of his degree coursework. Although it was

only a demo, it is wonderful quality, made in the Cathedral, and features

Michael singing 'In the Bleak Midwinter' . Again, a precious possession for us

now. That Christmas, BBC Southern Counties Radio recorded their Service of Nine

Lessons and Carols at the Cathedral, and Michael was lucky enough to have a big

solo which was heard all over the region on Christmas Eve and again on Christmas

Day. He may not have lived for long but far more people heard him sing than

have heard me play the piano, I should think!

Chapter 7

Looking back

on 1999 now has a special poignancy; the last year in which Michael was well -

at least for the most part. January was a special month because on the 16th

was my 40th birthday.

I was 18 on a

Sunday, and didn't have a party. I was 21 on a Wednesday, the first day of term

at Royal Holloway College, where I was studying, and I had a few friends in my

room for cake and champagne, but nothing wild or hedonistic. When Graham and I

were married, on October 16th, 1982, we had a relatively small

affair, with around 50 people, and a lunchtime reception in the College Picture

Gallery. No late-night disco or other extravagant largesse! On my 30th

birthday I was 8 months' pregnant with Christopher and I had a sedate evening

at the local Toby Carvery for a few friends, as I was unable to do anything

more than waddle about like Moby Dick's big sister. I remember working out as

quite a small girl that my 40th birthday was going to be on a

Saturday, and after this series of quiet celebrations I had every intention of

pushing the boat out. Graham was also going to be 40, in April, but we decided

to have a weekend away for his birthday and to celebrate and blow away the

post-Christmas cobwebs in style.

The boys were

very excited about this, and we spent much of 1998 deciding how exactly we were

going to organise things. We chose a venue and caterers, but Michael and

Christopher were keen on a theme. As musicians, we thought we ought to think of

something related and finally my love of jazz proved the key influence. We

decided to hire a proper 1920's jazz band - the 'Black Bottom Stompers' - and

once that had been settled the rest fell into place. The theme was black and

white, and rather than insist on black tie we simply put 'Dress: Black and

White' on the invitations. Which was how we came to have Morticia Adams, Elvis

Presley, two Mint Humbugs and a giant panda present at the celebrations.

This hadn't

really occurred to me as an option, having chosen a sensible black and white

evening dress, but Graham fancied going as Dick Turpin ( Dick Turnip according

to Christopher ), and the boys thought they ought to have a costume, too. So

down we all trekked to the fancy dress shop. I spent half an hour trying to

persuade the two of them to go as a pantomime cow, but there were such

arguments as to would be the respective halves that I simply gave up and

allowed them their own choices. Or rather I prayed they wouldn't choose

anything too overtly offensive.

Christopher

gave away a little of himself at this point by choosing a Fred Astaire outfit,

complete with cane. He looked incredibly dapper and I was just congratulating

myself on having such a suave and urbane child when he produced a little

moustache and announced he was actually supposed to be Charlie Chaplin. He'd

certainly perfected the walk.

Michael gave

away even more of his own nature. I was amazed when he emerged from the

changing room dressed as - a monk. At least, I thought he was a monk. He then

turned round, and I saw he had a skull mask and was clutching a scythe. Yes, he

came to his parents' fortieth birthday party dressed as the Grim Reaper. This has

a totally different overtone now, of course, but at the time it was simply

Michael showing his rather unsavoury sense of humour about the fact that he

regarded Graham and I as unacceptably over the hill.

It was a

wonderful party. Everyone who had ever meant anything to either of us was

invited. There were people there whom we hadn't seen for years - and many of

them hadn't seen the children since they were tiny, if at all. The boys had a

terrific time, dancing, eating and being irritating - but they spoke to

everyone there and that meant such a lot to us once Michael became ill, because

ALL of our friends had met him and understood so much more clearly what we were

going through.

The music was

a real feature of the evening. Although I had hired a professional band, I had

invited the Royal Grammar School Jazz Band to come and play for the first hour